Often, when we ask ourselves what is the price we pay for something, we don’t ask what we play for, that is, the benefit, the necessity, the attraction, the frivolity in play? We are a nation, even a world which loves to play, or in many cases, to pay enormous amounts to enjoy watching others play.

I am curious about what ways each of us play. For me, writing is a form of playing—with ideas, with notions, which transcend the ordinary round of daily life, for satisfaction, even for identity. It is not too much to say that we identify ourselves by what and how we play; but not to play, to leave space for play, is to live a fractured life, for play is a necessity for our own development as well as the culture we take part in shaping.

A book I read years ago and have returned to as a guide on play is by Johan Huizinga: Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Originally published in German, it was translated into English by the author shortly before his death. He suggests play can be an effective way of knowing. Here we are speaking of play that goes beyond table tennis—though that too has its play space.

However, play can take us deeper into what we know so we can uncover what we don’t know. We can also hit periods in our life when we lose a sense of play; when this has happened to me, I felt an emptiness, a vacuum in part of my emotional life that play once nourished.

I have also had friends say that what they have been doing to “make a living” has grown dull and boring. One said to me: “I think I have played this job out.” Then what? Suffer through to retirement, to pension-land?; or to change, to risk, to play with options, to imagine, perhaps, what one has always wanted to do but the monster, “practicality,” inhibited it.

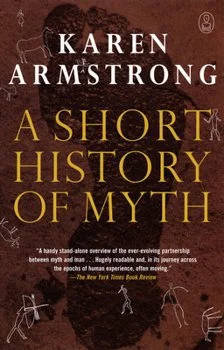

Perhaps we sell ourselves short when confronted by an obstacle, a “dead-end,” in life by attempting to find a solution through logic instead of a sense of play. In Karen Armstrong’s superb little book, A Short History of Myth, she writes that “play is a path to understanding, though perhaps obliquely, round-about, not head-on.” Perhaps seeing something or someone by indirection, playfully, might be more fruitful.

We should also remember, as you already know, that animals too have an instinct for play. Witnessing animals play with one another, with a ball of yarn, with a rubber bone that is thrown by a dog’s owner, is also entertaining and even joyful. We can also play by proxy.

Sorry for so many titles, but this next one by a medical doctor, Stuart Brown, is called Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. Early on he declares what we know: “you never really know what’s going to happen when you play,” adding that “play is the essence of freedom.”

Brown has learned from neurology that “play connects disparate maps in the brain.” Even more startlingly, he poses the question, “What difference does play make?” with a wondrous response: “The truth is that play seems to be one of the most advanced methods nature has invented to allow a complex brain to create itself” (my emphasis).

He then lists what is evoked in play: “anticipation, surprise, pleasure, understanding, strength and poise.” Play invigorates us to live a more fully satisfying life, when we lean into playing around with play.